12th November 2025

In this personal reflection piece, the HLA’s Ka Man Parkinson charts a six-month research and learning journey into the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) across the humanitarian sector. As research co-lead, Ka Man explores some of the nuance and complexity of the findings – intertwined with broader localisation and humanitarian leadership challenges – and calls for coordinated action during this crucial window.

In May 2025, the Humanitarian Leadership Academy joined forces with Data Friendly Space to conduct what we believe was the world’s first comprehensive study into how humanitarians are using AI in practice.

The original aim was simple: to tap into our global humanitarian networks to capture and share AI adoption data and evidence with the sector to help inform and support decision making in a rapidly developing area. What this generated in terms of data and sectoral response was beyond what we anticipated.

As our research co-lead Madigan Johnson from Data Friendly Space shared in our reflective podcast conversation after the report launch:

“It felt like we had tapped into this massive underground conversation that was just bubbling and waiting to come up to the surface.”

The demand for evidence-based, humanitarian AI guidance is clear

Six months since this initiative began, the research and outputs have received global engagement, including:

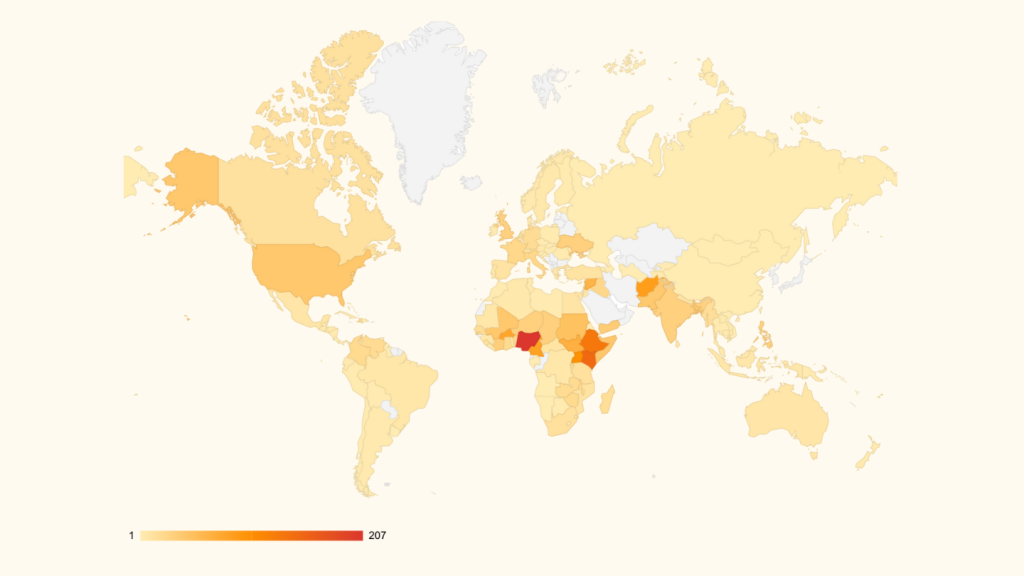

- 2.5k survey responses from 144 countries and territories

- An online report launch event reaching 739 attendees from 92 countries, and over 100 questions submitted to the panel

- A follow-up podcast miniseries focusing on global and African perspectives, reaching 80 countries so far

These metrics represent an unmet global demand for learning, information sharing, and knowledge exchange on a rapid development that has reached the sector at a time of profound crisis.

The engagement tells the story of thousands of humanitarians around the world – including those from communities affected by the most severe crises – who are driven to explore, learn about, and engage with AI tools to see if and how these can support their vital work.

Unpacking the key research theme: the Humanitarian AI paradox

At the heart of our study is what we call the Humanitarian AI paradox: the gap between widespread individual AI adoption and organisational readiness, combined with mixed attitudes on AI effectiveness.

- 93% of respondents use AI tools; 70% use them weekly or daily

- 70% who are using AI to support their work are using commercial tools like ChatGPT, Copilot and Claude

- Only 4% consider themselves to be expert AI users

- Just 8% report that AI is widely integrated in their organisations, and 22% have formal AI policies

- Less than half feel AI has improved efficiency

- Only 38% believe AI has led to better decisions

This snapshot presents a picture of a sector in transition: individual AI adoption is high, driven more by accessibility than conviction, and expertise and infrastructure lag behind. Organisations often lack the policies, training, and systems to scale responsibly.

Addressing high individual demand and sectoral supply of contextualised humanitarian AI

When viewed through an economic lens, the Humanitarian AI paradox can be seen to represent the gap between individual demand and institutional and sectoral supply of humanitarian-specific AI systems and support mechanisms.

While demand for humanitarian AI capabilities is evident in widespread individual commercial AI tool adoption, the supply of support mechanisms such as funding, tools, training – from funders, organisations, and technologists – has not kept pace with the development of appropriate infrastructure, governance, training, and contextualised tools.

It is highly encouraging to hear the recent announcement of a major funding initiative from a broad coalition of philanthropic leaders: Humanity AI, a $500 million five-year initiative “dedicated to making sure people have a stake in the future of AI.”

This funding signals recognition of the support gap, which I believe should be part of broader interventions to address supply-side challenges, redistribute power and decision making across the AI supply chain, and advance localisation by shifting influence from the Global North.

As Timi Olagunju, a governance expert from Nigeria speaking on our podcast said:

“I think it’s important that we look at the core context of capacity for the Global South, and also shared control. And by capacity, I mean real funding of the Global South, in terms of universities, labs, and startups, to actually build, test, and deploy AI models that are localised.”

AI decisions: a humanitarian leadership decision

When we originally embarked on this research exercise, we aimed to potentially uncover different innovative AI use cases across the sector to complement and build on existing information in this area such as the UK Humanitarian Innovation Hub (UKHIH) directory of AI-enabled humanitarian projects.

Yet what our survey uncovered was more experimental and emergent, while also creative and entrepreneurial. For example local leaders in the Global South creating their own mini ecosystem of tools to support them in their work: ChatGPT for reports, Google Translate for communication, specialised GIS tools for mapping, Power BI for analytics, and more.

What emerged and was captured in the adoption snapshot highlighted the creative thinking, application and adaptation behind the choices, more than the systems themselves.

As our research co-lead, Lucy Hall from the HLA reflected:

“What’s really come out strongly is the human element of artificial intelligence. It’s not around technology, it’s around leadership, it’s around organisational capabilities and capacities, and it’s around psychological safety.”

At the HLA, we know from our work and previous research with our global community and networks that humanitarians are highly resourceful, resilient and motivated to learn and upskill, even in the absence of organisational support. So this individually-driven AI learning and experimentation tracks with the trends and behaviours we already observe.

Humanitarians working in local organisations demonstrated high levels of interest and experimentation with AI, with the highest number of survey respondents from countries experiencing protracted crises including Nigeria, DRC, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Sudan, Afghanistan, Syria, and Burkina Faso.

As expert panellist, senior independent humanitarian leader Ali Al Mokdad remarked during the online report launch event:

“What we saw in this survey, or when we see people in the sector practising and using those different tools, it’s mainly enabled by a mix of different elements: pressure, accessibility and access, evidence, and adaptation.”

Moving from mapping current practices to future potential

The main report was launched in August 2025, and as we tracked the findings being disseminated across the sector through online engagement and commentary on platforms including LinkedIn, we found the key insight that gained traction was the gap between individual usage and organisational adoption.

This bottom-up adoption pattern driven by a surge in individual adoption enabled by tools like ChatGPT is beneficial in many ways in terms of supporting individual workflows and processes, as well as developing AI literacy. Yet at the same time it represents both organisational opportunities and risks for leadership teams.

Shifting from ‘Shadow AI’ to organisationally-led conversations and learning

Through our research, we found many respondents felt uncomfortable or unable to openly discuss AI use, which was often driven by individual experimentation rather than organisationally-sanctioned use – so-called ‘Shadow AI’ – creating clear governance challenges. This is intensified by 2025’s deep funding cuts and structural changes, which make open dialogue difficult.

Encouragingly, we are noticing a shift. Since we conducted the research, we have been receiving requests from organisations for presentations and discussions, and we are hearing from teams that they are piloting sandbox sessions, prompt-a-thons, and learning environments to enable safe, organisationally-led experimentation. However, this is an observation from our own conversations, which needs to be tested through follow-up research in 2026 to see if this reflects a broader trend.

Possible pathways forward: insights from expert conversations

What is next in terms of possible pathways forward together?

In September-October 2025, I built on the research and produced a deep dive podcast series to explore the key themes in further detail. This series features Global and African expert perspectives, since 46% of research respondents were from Sub-Saharan Africa.

From these conversations with experts across the sector, several practical priorities emerged that I believe have applicability across contexts.

For practitioners and organisations

- Start with AI literacy

A key message that emerged throughout the series: demystify AI for everyone, not just technical staff. Invest in skilling and training opportunities across all levels of the organisation.

- Establish data governance now

Treat your data responsibly. As Timi Olagunju advises: “Treat your data like cash” – secure it, track who accesses it, and only collect what you need. Develop an AI policy as a living document, using templates as a starting point but always localising and contextualising content.

- Begin with pain points, not possibilities

Identify organisational challenges first, then assess whether AI can help – rather than adopting AI and searching for applications.

As Deogratius Kiggudde said:

“Let’s invest more in learning how to use the tools effectively and efficiently by first identifying our biggest pain points in achieving our missions and objectives. Once we list those pains, then let’s work out what AI can do with those tasks.”

- Explore beyond ChatGPT and LLMs

Explore nuanced and contextualised solutions, not just the dominant technologies like large language models (LLMs) while others are looking ahead to the potential of agentic AI.

Three of the experts independently pointed to small language models (SLMs) as a specific approach for humanitarians, offering promising potential for contextualised humanitarian AI solutions, overcoming some limitations of LLMs, especially in low-connectivity or resource-constrained environments.

- Keep humans in the loop

AI should assist decision making, not replace it. Maintain human oversight, particularly for high-stakes or sensitive decisions and build frameworks to support human decision making and intervention.

Michael Tjalve emphasised the importance of taking a systematic approach to risk mitigation:

“It’s incredible what the AI models can produce today, but they will always make mistakes. Understanding how and when they can happen, so that you can proactively implement mitigation strategies, is important, but also to understand, for example, what the cost of those errors may be.”

For developers and system builders

- Enable localised, contextual solutions

Design tools to reflect local languages, infrastructures, contexts, stories and lived experiences. Build through local partnerships and appropriate technologies.

- Make community ownership and governance central

Communities should be able to shape, control, and sustain their own tools, whether through open-source approaches, participatory design, or other inclusive models.

Processes should align with cultural context. A core principle emerged: do not take more than necessary, whether that means data collection or resources.

As Wakanyi Hoffman said:

“Ethical AI simply means building what is needed and necessary. Not every problem requires a technological solution.”

And critically, always consider non-AI pathways. Analogue approaches may be the best fit, and we must avoid technological determinism – the assumption that technology alone will deliver the right outcomes.

Sector-wide considerations

- Foster genuine collaboration

With shrinking resources, collaboration should go beyond funding to include shared expertise, infrastructure, testing spaces, and connections. Coalitions of actors across industry, academia, governments and NGOs can help to balance risk and drive innovative approaches. AI adoption must happen in alignment with localisation processes.

- Document and share openly

Both successes and failures – and everything in between – are valuable. Public testing and open documentation accelerate collective learning and sector-wide developments.

- Develop pragmatic approaches to overcome paralysis

Running through these conversations was a consistent thread: the need for pragmatism to overcome paralysis. The experts I spoke to advocated for practical approaches that address on-the-ground realities – from norm-setting and guidelines to address data and AI governance challenges, to solutions-driven and community-focused collaboration.

Looking ahead: support mechanism prioritisation explored at the NetHope Global Summit

In October 2025, at the NetHope Global Summit in Amsterdam, the team and I facilitated two workshops to explore how to prioritise interventions to support humanitarians who wish to move along their AI adoption journey.

In the room together with technologists, funders, INGOs and local organisations from around the world, we explored the top priorities expressed by survey respondents: training and capacity strengthening, access to tools and platforms, and funding and resources.

While there was alignment that addressing supply-side gaps is critical, within the groups no clear consensus on sequencing or prioritisation emerged.

While there were overlaps, the choices were dependent on many factors including the lens through which the issue was examined – whether from the perspective of the practitioner, an organisation, or location.

Through these expert conversations in the podcast series and the workshop discussions at NetHope, one insight became increasingly clear: the interconnectedness of each AI dimension. There is no AI without data, no governance without literacy, no literacy without learning and skilling opportunities. These dependencies create challenges in unpacking priorities and sequencing interventions.

This complexity means that blind spots are inevitable when we operate in silos. I believe that through an intersectional lens, partnership and focused action, we can collectively unlock solutions and pathways ahead.

Research as a key driver in this collective learning journey

Research – whether academic or rapid, community-centred like our approach – plays a key continued role in this collective learning journey. Our study is supporting further academic enquiry just months after its publication.

Encouragingly, we have heard from researchers and humanitarian practitioners located in Colombia, Germany, Switzerland, and Türkiye who have begun to use our research to inform their own studies into humanitarian AI, and building on the insights to advance scholarship in their own contexts. This excites the team and me since this was one of the aspirations of this initiative, and supports our personal and HLA’s mission to support locally led learning and action.

Notably, one survey participant – a practitioner at a local organisation in Türkiye examining AI ethics in humanitarian communications – presented research building on our findings at the International Humanitarian Studies Association (IHSA) conference in October 2025, demonstrating how inclusive research methodology can support participants in their journey to become knowledge producers.

Commenting on the research report, Gülsüm Özkaya said:

“The report showed me that a humanitarian communicator in another context might be using an AI tool or approach that I had never even considered. For me, the report didn’t just validate my research interests – it expanded them.”

Shifting the power: inclusive humanitarian AI development

My key question centres on power and who drives and shapes choices. Decisions over AI use, resource allocation, technology choices, access, and ethical considerations such as climate impact, mirror broader humanitarian leadership challenges.

Since before the Grand Bargain, humanitarian actors have grappled with meaningful localisation and how shifting power from the Global North to local actors can bear out in practice – and AI deployment without coordinated and intentional efforts risks exacerbating localisation challenges.

But I want to hold an optimistic view, particularly following the partnership and collaborative spirit evident at the NetHope Global Summit. As we head into 2026, this relatively early phase of AI adoption offers a critical window to make decisions that shape humanitarian AI and strengthen localisation.

The recently announced partnership between Start Network and NetHope to advance digital transformation for local and national NGOs demonstrates growing recognition that local humanitarian organisations must be centred in discourse and decision making around digital transformation.

This can only be achieved through active cross-sectoral cooperation and the kind of convening spaces where local actors, frontline responders and community members can actively feed into and shape the agenda through genuine dialogue and inclusive processes.

At the Humanitarian Leadership Academy, our work continues to support the sector in this area, including convening actors and helping facilitate shared learning. To build on our 2025 baseline study, we plan to repeat the research in 2026 to track any shifts in AI adoption patterns, attitudes and aspirations.

In a video message broadcast in the room at the NetHope Global Summit, Jan Egeland shared that at the Norwegian Refugee Council they live by the ‘Kivu test’: will what we are doing bring improvements to, for example, women in Kivu regions of DR Congo? If not, then we shouldn’t do it. It’s an important reminder of what we’re here for and the communities we serve.

This is a moment to shift power, share resources and decision making, and enable the development of contextualised, ethical AI that actively supports localisation processes. Because ultimately, humanitarian AI adoption is not just a technical challenge – it’s a leadership decision about whose voices shape the future of our sector.

About the author

Ka Man Parkinson is Communications and Marketing Lead at the Humanitarian Leadership Academy. With 20 years’ experience in communications and marketing management at UK higher education institutions and the British Council, Ka Man now leads on community building initiatives as part of the HLA’s convening strategy. She takes an interdisciplinary, people-centred approach to her work, blending multimedia campaigns with learning and research initiatives.

Ka Man is the producer of the HLA’s Fresh Humanitarian Perspectives podcast and leads the HLA webinar series. Currently on her own humanitarian AI learning journey, her interest in technology and organisational change stems from her time as an undergraduate at The University of Manchester, where she completed a BSc in Management and IT. She also holds an MA in Business and Chinese from the University of Leeds, and a CIM Professional Diploma in Marketing. Ka Man is based near Manchester, UK.

Acknowledgments

With thanks and appreciation to all research participants who generously shared their experiences and insights; research co-leads Lucy Hall (HLA) and Madigan Johnson (Data Friendly Space); launch event panellists Ali Al Mokdad (independent), C. Douglas Smith (Data Friendly Space), and Dr Cornelia C. Walther (Wharton School/Harvard University); podcast guests Wakanyi Hoffman (Inclusive AI Lab), Deogratius Kiggudde (Carnegie Mellon University Africa), Timi Olagunju (The Timeless Practice), and Michael Tjalve (Humanitarian AI Advisory/Roots AI Foundation); and researcher Gülsüm Özkaya (Children of Earth Association).

Note

This article is a personal reflection, prepared to promote learning and dialogue. It is not intended as prescriptive policy advice. Organisations should conduct their own assessments based on their specific contexts, requirements, and risk tolerances. This research initiative was conducted independently by the Humanitarian Leadership Academy, in partnership with Data Friendly Space, and received no external funding.