23rd January 2026

Bringing people together to solve a problem sits at the heart of the Humanitarian Leadership Academy’s work.

Through initiatives such as the Humanitarian Xchange, the HLA creates spaces where people with different expertise, backgrounds, and perspectives can come together to tackle complex humanitarian challenges. By reducing hierarchy, removing titles, and focusing on the problem at hand, these spaces enable locally owned solutions to emerge.

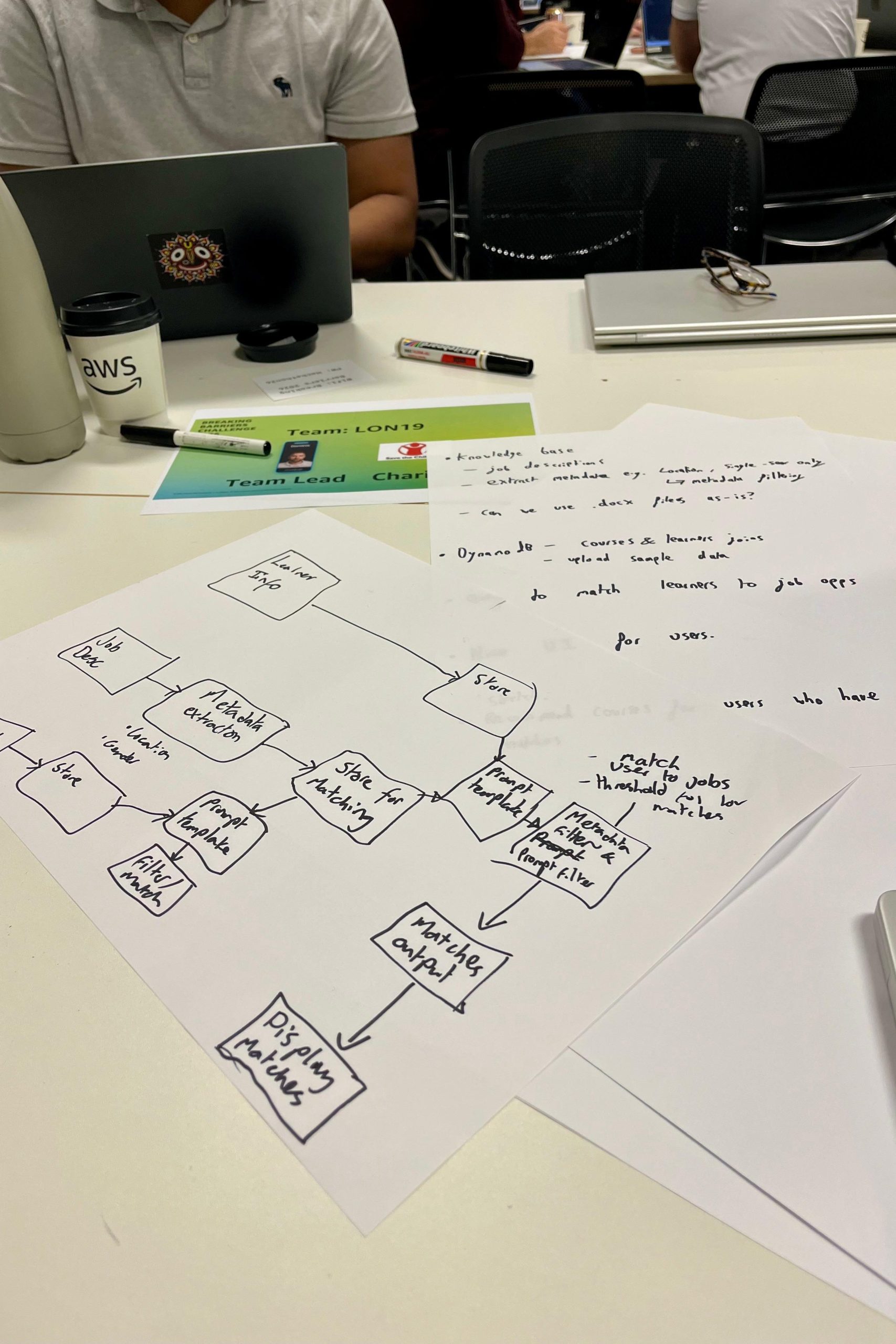

This approach was powerfully reinforced during the recent AWS Breaking Barriers Hackathon, where charities, technologists, and researchers collaborated to explore how technology — particularly AI — could support humanitarian problem-solving.

At a time when global narratives are increasingly shaped by division, fear, and scarcity, the hackathon offered a compelling reminder of what becomes possible when skills, curiosity, and collective purpose are mobilised intentionally.

Why we came: Kaya Match as a problem to solve

The HLA entered the hackathon with a clear challenge: how might we better connect humanitarian talent, opportunity, and local leadership in ways that strengthen — rather than undermine — locally led humanitarian action?

This question sits at the heart of Kaya Match, the HLA’s work exploring how technology can support more equitable access to opportunity, recognition, and pathways for humanitarians working in and from crisis-affected contexts.

Rather than approaching Kaya Match as a purely technical product, the hackathon offered an opportunity to test a broader hypothesis: that collective problem-solving, grounded in solidarity and service, can help reimagine how humanitarian systems function.

Collaboration without hierarchy

The HLA arrived at the hackathon as a multidisciplinary team, spanning data, research, communications, and business development. Working alongside technologists from AWS, the BBC, Experian, universities, and other institutions, it quickly became clear that collaboration flourishes when hierarchy gives way to shared purpose.

Ideas moved rapidly from concept to prototype. Knowledge flowed freely. Questions were welcomed. Expertise was shared without ego. Rather than reinforcing professional boundaries, the environment encouraged learning, iteration, and refinement in real time.

What was developed over three days demonstrated how quickly progress can be made when people are given the space, trust, and permission to work differently.

Mobilising people, not just roles

One of the most striking lessons from the hackathon was the importance of mobilisation.

The humanitarian sector has long excelled at mobilising specific roles and technical functions. The hackathon highlighted the potential of mobilising people more broadly — including those whose expertise sits outside traditional humanitarian pathways.

Participants consistently expressed a willingness to contribute time, skills, and energy to humanitarian challenges. This reinforces the importance of designing inclusive entry points for collaboration, where diverse forms of expertise are recognised and valued.

This thinking closely aligns with the HLA’s wider work on community-based leadership, youth engagement, and peer-to-peer learning — approaches that centre distributed knowledge and collective action rather than narrow definitions of expertise.

Technology as an enabler, not a solution

Technology featured prominently throughout the hackathon, but not as an end in itself. Instead, it functioned as an enabler — reducing friction, supporting rapid iteration, and allowing ideas to be tested within real-world constraints.

Teams worked with limited resources, imperfect data, and ethical considerations familiar to humanitarian contexts. Rather than defaulting to complex or costly solutions, participants prioritised free or low-cost approaches that could realistically be adapted and scaled.

This pragmatic, constraint-aware innovation reflects the type of problem-solving the sector increasingly needs.

Risk, experimentation, and the responsibility to evolve

We often speak about innovation and evolution in humanitarian action, yet in practice remain deeply risk-averse. Governance structures, funding models, and institutional incentives frequently reward caution over curiosity, and incremental change over meaningful shifts.

The hackathon offered a rare alternative: a well-governed, time-bound space where experimentation was encouraged, failure was treated as learning, and ideas could be explored without fear of immediate rejection.

If humanitarian action is to keep pace with the scale and complexity of today’s challenges, we must become more intentional about creating these kinds of spaces — not as exceptions, but as part of how we work. Responsible risk-taking is not a threat to humanitarian principles; it is essential to their survival.

Who gets access to innovation spaces?

The hackathon also raised a necessary question: who gets access to spaces like this?

For many local humanitarian organisations, opportunities to collaborate with technologists, data scientists, and researchers of this calibre are rare or entirely inaccessible. Yet these organisations are often closest to the problem and best placed to shape effective solutions.

If the sector is serious about locally led humanitarian action, then local humanitarians must have access to the same kinds of collaborative, high-quality problem-solving spaces that international organisations and large institutions benefit from. Concentrating innovation in a small number of global centres risks reinforcing existing inequalities.

Convening, brokerage, and solidarity in practice

Collaboration of this nature does not happen by chance. It requires trust-building, brokerage, and intentional convening across sectors.

AWS played a critical role in enabling the hackathon — not by directing outcomes, but by creating the conditions for connection between humanitarian actors, technologists, and private-sector expertise. As humanitarian challenges grow in scale and complexity, this brokering role becomes increasingly important.

The HLA is proud to work within an ecosystem of partners committed to connecting people, ideas, and expertise across borders — and to extending these opportunities beyond traditional centres of power.

From prototype to practice: Kaya Match as a commitment

The hackathon was not an end point. It was a starting point.

The next phase of Kaya Match will focus on taking the thinking, learning, and early prototypes developed during the hackathon and working directly with local humanitarians to test, challenge, and build them further. This means grounding development in lived experience, ensuring it responds to real needs, and shaping solutions with those closest to the context — not for them.

For those of us with access to power, privilege, and spaces such as global technology convenings, there is a responsibility to use that access in service of others — to broker connections, remove barriers, and share risk.

Locally led humanitarian action must remain the centre of gravity. But locally led does not mean locally isolated. When global expertise is mobilised in humility and accountability, it can strengthen — rather than dilute — local leadership.

This is the kind of solidarity the sector needs: collective problem-solving that serves those leading change on the ground.